General Information

Building Name: United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

Bulding Location: Washington, D.C., United States

Project Size: 254,000 gsf, (154,000 sf. conditioned, 100,000 sf. garage)

Building Type: Office/Public Assembly

Project Type: New Construction

Delivery Method: Integrated Project Delivery

Total Building Costs: $110,822,619 Cost/ft²: $436.00/sf

Owner: United States Institute of Peace

Project Completion Date: October 25, 2010

Date Building Occupied: March 21, 2011

Project Team

Architect

Safdie Architects

100 Properzi Way

Somerville, Massachusetts 02143

617-629-2406

www.msafdie.com

General Contractor

Clark Construction Group, LLC

7500 Old Georgetown Road

Bethesda, Maryland 20814

301-272-8100

www.clarkconstruction.com

Structural Engineers / MEP Engineers / Sustainability

Buro Happold Consulting Engineers, PC

100 Broadway

New York, NY 10005

212-334-2025

www.burohappold.com

Glazing and Roof Design Assist

Seele, Inc.

Gutenbergstrasse 19

86368 Gersthofen Germany

+49 821 2494 - 0

seele.com

Landscape Architect

Balmori Associates

584 Broadway, Suite 1201

New York, NY 10012

212-431-9191

www.balmori.com/

Project Management

Stranix Associates, LLC

1802 Pillory Drive

Vienna, VA 22182

703-281-2379

www.stranixassociates.com

Owner Contact

William F. Rothenbecker, Associate Vice President for Operations

United States Institute of Peace

2301 Constitution Ave. NW

Washington, DC 20037

202-429-7970

wrothenbecker@usip.gov

USIP

Facility Management

Akridge

Jennifer Kienel, Sr. Facilities Manager

jkienel@akridge.com

www.akridge.com

DESCRIPTION

The U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) was created by the U.S. Congress in 1984, in the shadow of the Vietnam War and at a time of ongoing Cold War tensions. Its mission is to prevent, mitigate, and resolve violent conflicts around the world by engaging directly in conflict zones and providing analysis, education, and resources to those working for peace. The vision of the Institute is a world without violent conflict. During its initial two decades, the Institute operated without a permanent facility, in nondescript commercial office space. But as the work of the Institute demonstrated its value to the country, Congress concluded that the organization warranted a permanent facility at a significant location in the national landscape.

When discussions first began in 1992 to launch the new USIP Headquarters in Washington, DC, a vision of the future began, not only for the advancement of international peacebuilding, but a strong commitment to a design that would include environmentally sustainable features and technology, setting the tone and serving as a model for future federal facilities.

LEED Gold plaque on display at the Institute

The project, a 254,000 gsf, five-story facility designed by internationally renowned architect Moshe Safdie and built by Clark Construction, had an initial goal to achieve LEED Certification under the U.S. Green Building Council's rating system for New Construction. But through the support and teamwork between the Institute's project team, the architect, and Clark Construction, a "whole building" design approach was taken, and USIP surpassed its initial goal and achieved LEED Gold Certification when it opened in March 2011.

The whole building approach also helped to meet the economic and environmental interests of all groups involved. The project quickly launched as a leader in implementing sustainable and cost-effective design, joining the ranks of federal sustainable buildings, efforts that are paying off—literally. The USIP Building performs 23.16 % better than ASHRAE 90.1-1999 requirements using the LEED Energy Cost Budget methodology which also earned the project 2 LEED points.

Paul Gross, the Project Manager for the architect, Moshe Safdie, and Richard Solomon, USIP President from 1993–2012, meet during construction on the 5th floor bridge.

The site, formerly a parking lot and one of only a few remaining building sites near the National Mall, is located adjacent to the former US Navy Bureau of Medicine and Surgery between Constitution Avenue and 23rd Street NW. On visual axis with the Theodore Roosevelt Memorial Bridge, the proposed Institute headquarters provided an opportunity to develop a new urban gateway to the District. The site forms a pivotal corner as the Mall expands toward the Potomac River. Given this location, the building would not only provide an enriching and uplifting environment for its many activities—scholarly, administrative, and public—but also represent the nation's commitment to the peaceful resolution of international conflicts by its presence amongst the many monumental elements lining the National Mall. Surrounded by the Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln Monuments, the Institute's monumental structure is also now in view, with its sculptural roof, evocative of the wings of a dove, meeting visitors as they cross Memorial Bridge into Washington. The building represents an opportunity to contribute to the heritage of buildings of national import represented in the Capital.

View of the Institute with the Capitol and Washington Monument in the background.

The Institute in spring during cherry blossom season.

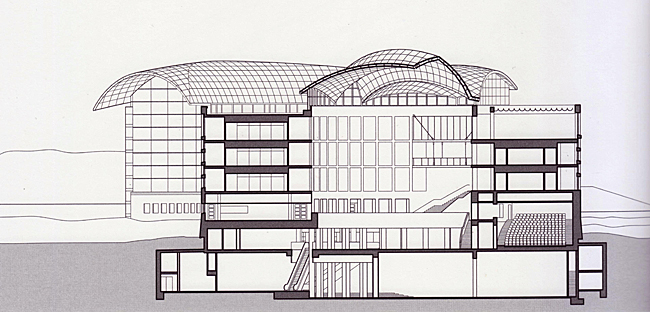

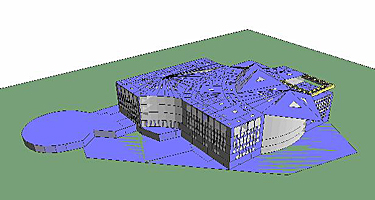

The overall development has a gross floor area of 254,000 gsf, with five floor levels above grade and two basement parking levels. The USIP project consists of one main building envelope with three distinct accommodation wings separated by a series of open atria spaces. These building areas are described below:

-

Wing A: Office accommodations from Level 3 to Level 5, with back of house ancillary space and parking from Level 2 down to Level P-2

-

The North Atrium: Open atrium space from Level 3 up to the exposed, translucent glazed roof

-

Wing B: Conference and office accommodation from Level 2 to Level 5, with back of house ancillary space and parking from Level 2 down to Level P-2

-

The South Atrium: Large open atrium space from Level 1 up to the exposed, translucent glazed roof

-

Wing C: Auditorium and office accommodation from Level 1 to Level 5, with back of house ancillary space and parking from Level 1 down to Level P-2

East-west section through the south atrium

Overall Project Goal/Philosophy

Moshe Safdie, the architect chosen by the Institute, set out to design the project to possess seven elements that would serve its mission. They include:

-

Inspiring workplace: The complex must provide an inspiring and uplifting work environment for the permanent and temporary users of the building as well as the public at large.

-

Interaction: The architecture should promote interaction and a sense of community among those who use the building. Its organization should act as a catalyst for spontaneous and unprogrammed interaction.

-

Symbol: In its physical presence and form, and given its setting at the northwest corner of the National Mall, the Institute's headquarters must become a symbol of peace set among the other symbolic structures nearby.

-

Light as a metaphor for peace: Natural light must permeate and endow each space within the structure. The building should be luminous every day and night and in all seasons.

-

Garden as a metaphor: The notion of the garden as a symbol of peace, paradise, and tranquility must inspire the design.

-

Harmony with nature: The tectonics and construction methods must form part of the expressive language of the building, demonstrating a responsible and inventive attitude toward conservation of resources and a natural economy of means.

-

Serenity: In its organization and spatial hierarchy, the complex must be self-orienting. It should form a sequence of processional routes to achieve optimal clarity. The architecture should radiate calmness.

ACCESSIBLE GOAL

The Institute was intended to be accessible both physically and symbolically. The goal was to have every aspect of the building be ADA compliant and make access and transitioning through the building a seamless experience. This was achieved by the use of elevators when stairs are not an option for users. The restrooms, water fountains, ramps, latch clearances, wheel chair and companion seating throughout the building, and the assistive listening system in the auditorium, support these goals in a way that is integrated and unobtrusive. The LULA elevator in the auditorium is an example of a high quality ADA mandated device that serves the disabled community without calling attention to their disability.

To the right of the stage in the auditorium is the LULA elevator, which allows disabled participants to access this level.

The curvature of the walls in the men's restrooms, due to constraints during construction, made it essential to incorporate push button door openers to meet accessibility requirements.

AESTHETIC GOAL

Safdie was inspired and influenced by the city's other monuments and monumental buildings, many of which are white limestone and represent the nation's struggles through wars as well as the ideals of democracy and a better world.

Significant buildings and monuments in Washington, DC were a source of inspiration for the architect Moshe Safdie's design of the Institute.

Left to right: Jefferson Memorial, US Capitol, and the Lincoln Memorial.

The qualities Safdie sought to achieve aesthetically were driven by the ideas and qualities of whiteness, lightness, and glow. His sense of the whiteness of the Jefferson Memorial represents purity and wholesomeness, while also appearing to be about order and authority. Whiteness is not only a Washington color; it is widely associated with peace, as in the celebrated white dove in Picasso's work. He was thinking of lightness as well. If mass and weight are associated with the architecture of power and authority, lightness is almost fleeting in character. It is in motion, with a sense of lift, or lightness of being. The architecture of lightness is contemporary; it evokes the world not of stone, concrete, or wood, but of glass and transparency. His exploration of glow considered the light, the light of translucent surfaces, sunlight glowing through the petals of a lily or rose, light glowing through a lantern, and light penetrating through a thin slab of marble or onyx. These ideas were made manifest through the extensive use of glass and light colored limestone. The building is over 70% glass and has 1,506 panes of white glass on the roof and another 378 in the clerestory and curtainwalls.

Bridges connect the wings of the building providing opportunities for conversation and views.

Awe-inspiring view looking up toward the roof from the Shultz Great Hall.

COST-EFFECTIVE GOAL

The project had a relatively modest budget. This meant that the architect and client had to make some difficult choices in the use of materials. For example, the atria floors are paved in honed limestone, but the curved walls of the grand spaces are sheathed in sheetrock.

The building had to be constructed through a collaborative procurement process that required competitive bidding. Due to the complexity of the glass and roof structure, this set the designers on the path of expressing their design intent in a set of documents that would be sent out for proposals to a list of qualified manufacturers specializing in glass structures.

Cutting the limestone flooring.

Finished flooring in the atrium.

The meeting rooms of the Negotiation and Conference center off the large atrium are equipped with state-of-the-art technology, such as videoconferencing. Carefully considered details make the most of smaller spaces: offices for the staff are not large but have high ceilings, glass clerestories, and side panels that admit extra light.

In sum, "the financing behind the headquarters, which was completed in 2011, says a great deal about how the world of publicly funded construction is changing and dramatizes how federal budget austerity has inspired creative private/public partnerships to deal with costs by innovative means." USIP's real estate strategy has proved to be an ideal model for the transition from leased to owned space. It has enabled the Institute to leverage facility user fees to cover the annual cost differential between former leasing costs and the new building's operating costs. (Urban Land Magazine, Urban Land Institute, May 23, 2014)

Left to right: Farooq Kathwari Ampitheatre under construction and completed.

FUNCTIONAL GOAL

The proposed headquarters would essentially need to accommodate the dual life it would serve. On the one hand, it was conceived as a very public building. It would accommodate ceremonial public spaces, an education center, Shultz Great Hall, a conference center, and an auditorium. In addition, the program also called for more private, contemplative spaces where scholars and researchers could pursue their studies and disseminate information throughout the world.

Images of peace activities undertaken by the Institute are on display to offer insight, inspiration, and lessons to visitors and staff alike.

USIP President Nancy Lindborg addresses a large group in Shultz Great Hall at an evening event celebrating 30 years of peacebuilding by the Institute.

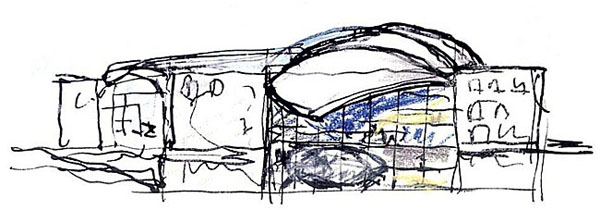

Safdie drew upon the architect LeCorbusier's belief that "the plan is the generator", by which he meant that the plan of a building embodies its organization and thus is the key to the emergence of a design. So the building's geometric order is a generator. It is through the geometry that the space and form of the Institute were to be comprehended.

One of Safdie's sketches for the Institute.

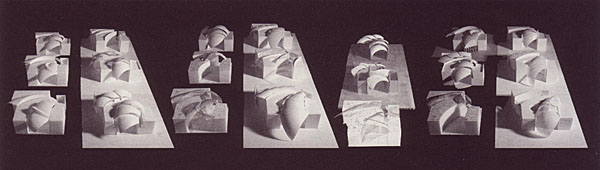

Safdie worked with models to reach the conclusion that the building should have two entrances and two interior organizing volumes, one for its public purposes and the other for business. This resulted in three wings, radiating from the upper corner of the site, and containing two voids. The larger void, an atrium, faced the Lincoln Memorial, and would be the center of public activity. The smaller void, facing the Potomac, would be the research-centered space of the building. Since the site descended two floors toward the Mall, there would be a dramatic view from the higher entrance on 23rd Street down to the conference center, toward Shultz Great Hall, which the large space open to the public was named, and the Global Peacebuilding Center. From the public entry, offices, and other working spaces would be visible. Underlying the designer's thinking was the desire to make the building truly interactive. An institution in which a wide variety of staff, resident fellows, and visitors interact must be designed so that its very nature fosters dialogue and exchange.

Building model studies of roof forms

The flexibility of the building has already served USIP and its mission very well. In 2014, the USIP Headquarters was selected to serve as the International Media Center for a three-day U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit at which President Obama welcomed leaders of Africa to the Summit, primarily to address economic issues. This was the largest Summit held by any U.S. President. Due to its close proximity to the State Department, as well as its ability to provide the services and secure, controlled facility access required for the role, the USIP facility offered the Summit a 254,000 sf, multi-purpose workplace and high-tech international negotiations and conference center, with a 230-seat auditorium and an 18,000 sf, open, exhibit area. Hosting the Summit required extraordinary management of the USIP Headquarters and systems to address this important international gathering, and the team demonstrated best practices that property professionals in both the public and private sectors can use when preparing their own properties for high-profile events.

The P2 Level of USIP before, and after, transformed for use during the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit.

PRODUCTIVE GOAL

Effective, efficient, and inspiring use of space meant creating the right environment for concentration, learning, communication, and collaboration for the staff and visitors of the Institute in a balanced manner. A mixture of enclosed offices and open work areas was preferred rather than a culture of all open workspaces. The two central atria would serve several purposes. They would allow daylight to penetrate nearly every working space in the building and would provide, even for the inner offices, views of the city. Additionally, the atria spaces were intended to encourage interaction. They provide places to share a lunch or have a conversation. Five levels of offices and conference rooms feature window walls that open onto the atria; in this way, work and activity in the building are not secretive but visible. There is a delicate balance between privacy and community. On the one hand, the majority of the building's inhabitants enjoy private offices; on the other, everyone is visible to each other across space, making each person aware that he or she is part of a greater whole. Ultimately, the purpose was to enable the headquarters to be a community of participants, echoing the Institute's larger mission in the world.

Left to right: Typical office, small conference room, and event demonstrate the range of space types at the Institute that allow for privacy, collaboration, and public engagement.

Offices and the cafe receive an abundance of natural light and have views to monuments and the city beyond.

SECURE/SAFE GOAL

A risk analysis was conducted to determine the level of security at which the building would be designed and constructed. With an average of one Head of State visiting the property every 78 days, security had to be addressed at many levels including the site and building elements. Additional security measures were added after the building was completed including a guard booth and vehicular barriers and bollards. Lighting was also a consideration from the perspective of both aesthetics and safety. Daylit spaces make it easier to evacuate in the event of a threat accompanied by a power outage. The desire to light the building at night needed to be balanced with how other major buildings and monuments were lit in the Washington, DC landscape while also providing needed security. The solution was to create a dimmable lighting program so that there would be no fixed lighting levels. Security lighting was designed in concert with automated sensing and surveillance systems which can improve detection capabilities while reducing the need for constant high nighttime lighting levels. The effect is a glowing building that is well lit and seen in the context of the other notable buildings and monuments in the surrounding area.

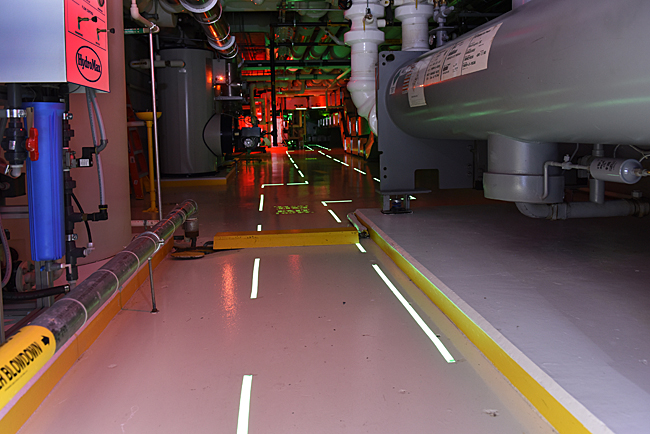

The escape route from the HVAC rooms is well lit with the help of fluorescent tape to guide the way.

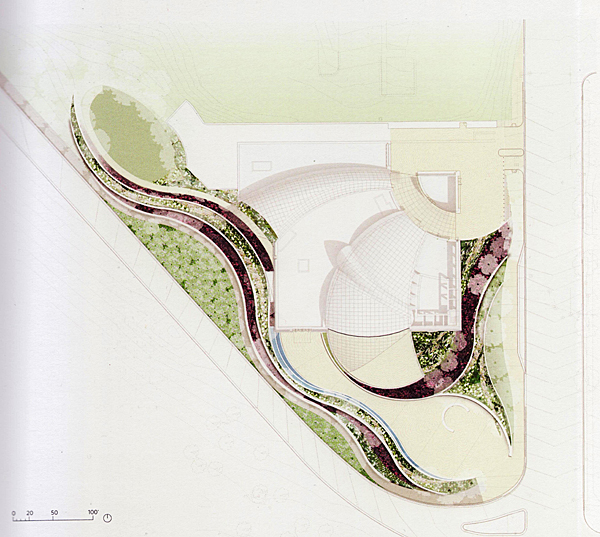

The Institute's landscape is designed as a garden that surrounds the large circular plaza in front of the building's main public entrance. This plaza is contained by semicircular benches and beyond, by "living walls" that separate the space from Constitution Avenue and 23rd Street, the two busy thoroughfares that intersect at the southeast corner of the site. These undulating concrete walls flow through the garden and paths at various angles and heights and are draped with plants or contain pockets of planting. By forming a broad, thick barrier, the living walls serve as a line of security around the building's perimeter and, by screening out the constant flow of traffic, increase the sense of distance between the garden and the street.

Landscape plan by Balmori Associates that also provides site security elements at the perimeter.

SUSTAINABLE GOAL

The original goal for the project was to achieve LEED Certification. But the project surpassed that to achieve LEED Gold. A whole building design approach was taken, meeting the economic and environmental interest of all groups involved with the project. Buro Happold was contracted early in the process to provide integrated engineering services and to investigate what was achievable in the Washington, DC region regarding LEED points and strategies. Performance metrics and standards, as well as review of peer building portfolios, served as part of the analysis during the early stages of the process. The complex geometry of the building required that the analysis address building loads and energy loads simultaneously so the layers of the building could be optimized. For instance, condensation and temperature ranges within the large atria spaces and skylights had to be considered to aid in the selection of materials, details, and finishes. USIP, Safdie, and Clark Construction were a part of the decision-making process engaging in reviews and approving proposed strategies along the way with incremental changes being made over time.

The simplest strategy employed to achieve a healthy, sustainable building was through the use of daylight. Additionally, the design incorporated high efficiency HVAC equipment, water-conserving fixtures, low emitting carpets, and low VOC paints and finishes. The HVAC systems are fairly traditional but designed to be smart and efficient through the use of controls. High ceilings and large windows let in more light and reduce the need for air-conditioning and heating. The light colored roof is reflective and the glass was fritted, both of which help decrease heat loads on the building. Construction and materials were locally procured and made to last, including the cast-in-place concrete and its reinforcing steel. These two materials also contributed to the local materials and recycled content LEED credits achieved for the project. The building is smoke-free and also incorporates green cleaning practices.

PROCESS

Overview of Process

The project was planned, designed, and constructed through a whole building integrated design process and integrated team process.

Pre-Design/Planning Activities

Three years before construction on the new headquarters began the team was assembled and contracted for their services. Early involvement was necessary to conduct the required research and planning on the project as well as raise necessary funds. Stranix Associates was engaged to provide project management and the Institute hired the firm MGA to develop the initial program, upon which Safdie was asked to base his design. Clark provided budgeting, constructability reviews, and value engineering from the schematic design phase through the construction documents, over the course of 29 months. These efforts resulted in a cost-effective GMP—a tremendous achievement given the extremely high level of complexity in the design.

Throughout the preconstruction phase Clark engaged multiple subcontractors in different trades to provide their expertise in guiding the design towards constructable ways to achieve the intent. This was an effective approach to identifying qualified subcontractors and increasing the subcontracting community's interest in the project.

Team meetings before and during construction to ensure close coordination and effective communications throughout the project.

Virginia Senator John Warner and former USIP Chairman of the Board, J. Robinson West, review construction progress.

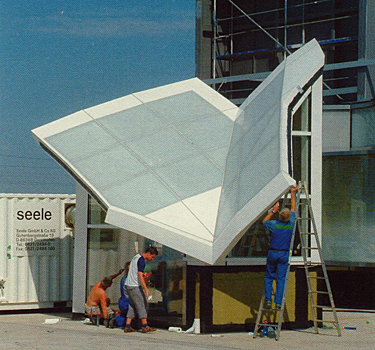

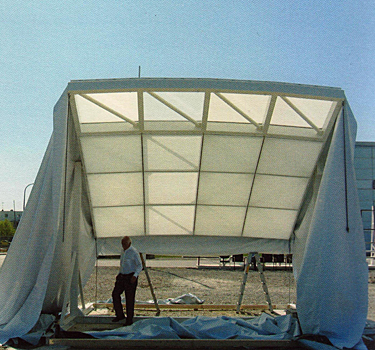

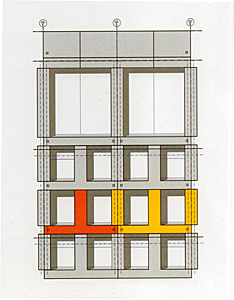

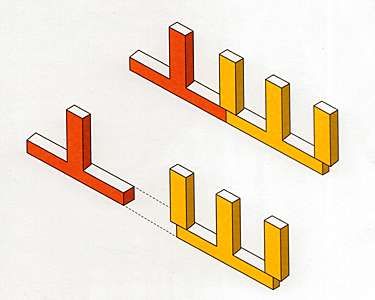

Clark also led a formal design-assist procurement for the custom glass roof and curtain wall on the project. The schematic design was competitively bid and the project team then managed the design-assist subcontractor, Seele, through the design process, including architectural modeling, structural check modeling and visual and performance mock-ups. The custom curved roof could not have been designed and constructed without the invaluable expertise of the design-assist subcontractor.

Design Activities

A project of this scope, complexity, and prominent location on the edge of the Mall, would of course have to receive the approval of the National Capital Planning Commission (NCPC) as well as the U.S. Commission of Fine Arts. The structure would help fill in the Northwest Rectangle, one of the areas NCPC was targeting for improvement in the National Capital Framework Plan. The organizations were engaged from design through pre-construction and NCPC approved the final site and building plans for the project. As a condition of approval, USIP was required to provide the Commission with a copy of the building manual, with content specifying final luminance limits for the building. This would help ensure that the building's lighting would defer to the Lincoln Memorial and not detract from the visual composition of illuminated memorials on the National Mall.

The search for the Institute's roof form was intense. Safdie's first sketches of the roof expressed a plurality, not a singularity. Some of the drawings resembled a flock of birds in flight, while others evoked a cascading cluster of domes, while still others looked like a series of hovering petals. They embarked on a series of studies using a vacuum-forming machine, in which objects can be used as molds to create transparent or translucent membranes. Several interpenetrating elements would form the roof, but they would all be made of segments of spheres and toroids. These forms were chosen because they are easier to build, analyze and fabricate. The sphere and the toroid enabled the roof's structure to be orderly and repetitive, and the glass panels allow for the consistent curvature of the roof. There was close coordination and continuous communication with Seele, who was chosen to construct the roof and was commissioned early on in the process. Seele developed many complex three-dimensional drawings, deploying the most advanced technologies of both design and fabrication. Mock-ups were built in Gersthofen, Germany, that utilized several types of glass, films, and framing. Along with representatives of the engineer, Safdie's team traveled to study the mock-ups, working with the Seele team until all the details were finalized. The finished roof strikingly demonstrates what can be achieved when old methods of procurement are expanded into new modes of collaboration between design and industry.

Visual and performance mock-ups constructed at Seele headquarters in Gersthofen, Germany.

Construction Activities

Self-Perform: Foundations: The excavation and support of excavation, performed by Clark Foundations, faced logistical challenges, but was completed within the four-month schedule. There was 90,000 cubic yards of excavation, of which 65,000 cubic yards was rock. Clark Foundations worked around buried utility lines and structures, a 72–inch diameter sewer line, and an existing seven-foot-high buried steam tunnel. The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) steam distribution lines supplying heat to government buildings in Washington, DC, run through the USIP headquarters. During construction, GSA allowed USIP to move the steam lines temporarily to make room for the new headquarters. USIP in return provided the government new steam lines through the USIP garage. GSA received the benefit of new steam lines, plus the bypass lines. The USIP campus also hosts a GSA steam house which is a pressure reducing valve station. Larger steam pipes come into the building, the pressure is stepped down and the steam is diverted to the buildings. At each building, the pressure is stepped down again.

The project's location, adjacent to the U.S. State Department and two U.S. Navy buildings, one of which is located just 10 feet from the sheeting and shoring line, proved to be a challenge for the project team during construction. Despite the large amount of rock excavation, Clark minimized disruptions to tenants in these neighboring buildings. A concrete structure, USIP Headquarters' atypical layout made flawless concrete work both essential and extremely challenging. The cast-in-place and precast concrete often met along radial grid lines, which required the Clark Concrete team to carefully match the precast panels. The roof's trellis, constructed entirely from architectural concrete, was cast using custom architectural forms and unique concrete vibration methods. USIP is proud that 75% of construction waste was diverted from landfills during the construction. The pre-cast concrete and glass were fabricated off-site. So this greatly reduced the waste scenario for the team during construction.

Constructing the retaining walls and the concrete façade.

Constructing the dove shaped roof elements.

Interiors looking toward the roof structure while under construction.

Operations/Maintenance Activities

USIP awarded the care and maintenance of its dramatic new headquarters facility to comprehensive real estate services firm Akridge, who was brought in early to facilitate the commissioning and start-up of building systems. A fully integrated team from the beginning was paramount in achieving and even surpassing USIP goals. The partnership between Akridge and USIP was immediate, "We feel fortunate and honored by USIP's selection of Akridge to operate this architectural symbol of the country's commitment to peace," said company President Matthew J. Klein. "We have assembled a 'best of the best' team that is inspired by the opportunity to take responsibility for this asset and manage it in a manner commensurate with the stature of USIP's organization and mission." It did not take long for USIP to get on the radar of industry professionals for its wicked efficiency.

Selected as 2015's Public Buildings Case Study for the Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) International magazine's "Operational Best Practices for a Competitive Edge" edition, USIP Headquarters is increasingly cited as a leading-edge model of local, national, and international architecture in both design and operations and management. A former Commissioner of the federal Public Buildings Service (PBS), who oversaw more than 1,500 federal buildings nationwide (350 million sf) and more than 175 million square feet of leased space supporting more than 1 million Federal workers, regards the USIP headquarters and its operations and management practices as "the model" for Washington's complex facilities management requirements. USIP got on BOMA's property management professionals' radar because PBS was studying USIP's Energy Star energy efficiency program for use in federal buildings and for the Institute's precedent-setting multipurpose transformation of the headquarters for helping host the 2014 U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit. (BOMA magazine, Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) International, January/February 2015)

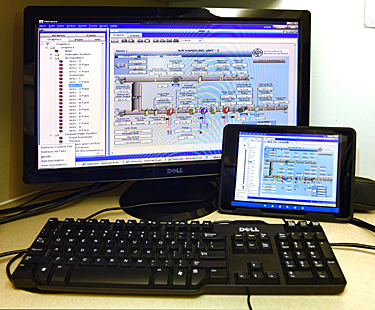

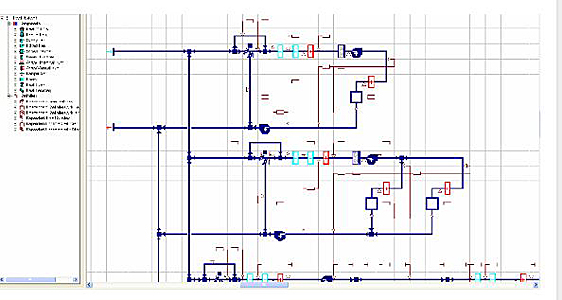

Data plays a very important role in how the Institute is managed. A suite of systems and monitors throughout the building lets engineers access real-time data on electrical, water, and gas consumption, alerting them to a problem or giving them sufficient time to react before a problem arises. If there is a large event being hosted in the building or if the day is unusually hot or cold, this type of monitoring can be especially helpful. The energy data benefits and supports budget preparations as well. For example, the facility team uses Web-based software to access real-time energy data to provide historical comparisons and assist with energy conservation measures.

State-of-the-art technology lets engineers control building automation systems (BAS), lighting, and other systems from anywhere in the building. Analysis is necessary in order to meet certain requests to make sometimes even a small change which can affect the sequencing of many systems. If an occupant complains that the main atrium is too hot, the radiant heating and cooling underneath the floor could sweat and damage the floor if the dew point is affected.

On a regular day at the Institute, without a large event, the building's automated systems control themselves and can basically run on "auto pilot". Its connectivity occurs across two systems. One controls the lighting and is linked through a processor to a computer that can be accessed remotely. The other is an energy management system (EMS) which monitors 13,000 points and runs within a separate, wireless system that communicates to a server in the engineer's office.

Computers in the engineer's office help manage and monitor the building and its systems.

Akridge engineers receive regular ongoing training at USIP to keep everyone educated and up to date on the building's systems and to ensure building efficiency.

P&R Enterprises, Inc. instituted LEED/Green Cleaning methodology from the first day that services were provided to the Institute. P&R Enterprises, Inc. is Green Seal GS–42 certified and CIMS-GB certified. The methodology deployed includes 4–Level filter vacuum cleaners, color coded microfiber cleaning cloths, all cleaning chemicals are green certified, all paper products for the restrooms conform to green certifications and all employees are trained in the proper use of these tools and products. Cleaning products used include:

- Alpha-HP Multi-Purpose Cleaner

- Glance NA Glass Cleaner

- Virex II

- GS Heavy Duty Pre-spray

- General Purpose Spotter

- Stride Neutral Cleaner

Post-Occupancy Evaluation Activities

The Energy Management Systems (EMS) can be reviewed on iPads as shown here, allowing for continuous or remote management.

USIP has maintained an Energy Star score of 91 or higher each year since 2012. As of October 2015, USIP proudly maintained the score of 91, meaning USIP performs in the top 9 percentile when compared to similar buildings as outlined in Commercial Buildings Energy Consumption Survey (CBECS) data. Even with the numerous after-hours events USIP hosts and challenging features, with over 70% of the building being constructed of glass, including the glass roof with nearly 1,506 white translucent glass roof panels, and a five-story curtain wall system at the front atria, the team is able to maintain this notable Energy Star score. Additionally, USIP is pursuing the LEED Dynamic plaque, and to date has a score of 73 (with one year to improve and lock in on the score).

The Building Automation System monitors over 13,000 points, which is almost unheard of with the average for most buildings being at 1,000 points. With a 25,000 sf. plant, the engineers leverage technology to manage complex building systems; important building changes can be one click away on iPads they carry to closely monitor the building and maintain efficiency.

Windows in the exit stairwells with sweeping views encourage staff to walk between floors rather than take the elevators, which aid in the offset of energy demands of using an elevator and contribute to employee health benefits by encouraging them to walk. An additional stairwell in the center of the building, spanning from the first floor to the fifth and highlighted by a rooftop skylight, provides an alternative to staff using the elevators.

Internal stairwells encourage walking between floors and offer views out to the city.

USIP earned 2 LEED points for Water Use Reduction by installing low-flow lavatory faucets and water closets throughout the building. This helped meet the 30% water use reduction requirements necessary to earn those points, exceeding the baseline numbers of the 1992 Energy Policy Act for fixture flow rates and performance requirements. USIP consumes only 162 kBtu/sq. ft.

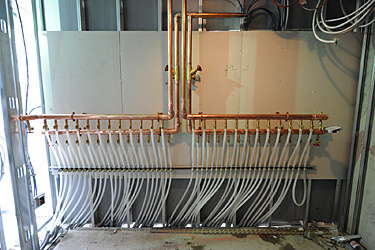

Unique features, such as the radiant floor heating and cooling running under the limestone floors help maintain comfortable temperatures in these wide open atriums, aiding in the reduction of energy cost as well as limiting the expanding and contracting of the extensive limestone floor.

Left to right: Setting the radiant floor heating and installing the limestone flooring over it.

Left to right: The radiant heating and cooling connection and system.

Two innovative complex lighting systems work in sync and a photocell monitors the amount of daylight, allowing for lights in specific common areas to turn off when daylight provides adequate illumination. A digital control system regulates lighting systems, turning them off in unoccupied spaces and allowing engineering to dim various lights for events.

Special lighting in effect at the Institute celebrating the 70th anniversary of the United Nations.

Additionally, occupancy sensors, electronic astronomical clocks, and electronic dimming ballasts save energy in daylit areas. USIP was designed so that each office features either an exterior window or an interior window, which overlooks the atrium below, meeting the ambient lighting requirements. This reduces the need for electric lighting, resulting in a substantial energy savings, while increasing employee productivity with the breathtaking, panoramic views of the Potomac River and National Mall, including the Lincoln Memorial, which feels as though it is only an arm's length away.

Left to right: The Lutron lighting system processor for the atrium, main processor.

Encouraging greener transportation choices, USIP is prominently situated across the street from a bus stop and within walking distance to a metro. Additionally, it was designed to include a protected and secure bike station in the garage, equipped with a bike service station. Showers and locker rooms are located inside the building for employees who ride to work; incentivizing staff to take an alternative form of transportation or bike to work. Special parking is reserved for those who carpool or drive a hybrid vehicle.

Parking sign in garage for low emission vehicles.

Bicycle storage encourages employees to use alternative forms of transportation.

With streamline recycling at USIP and recycling bins set up on every floor, including in staff offices, it makes it easy for staff to recycle. As IT hardware and other building equipment become obsolete or unserviceable, it is disposed of in an environmentally sound manner. Sixty-five percent of building waste was recycled in 2014. In 2015, USIP recycled over a ton of IT hardware and continues to work at keeping the recycling numbers high. USIP also purchases green power to earn renewable energy credits.

Recycle and trash cans on every floor encourage a high level of recycling.

INFORMATION AND TOOLS

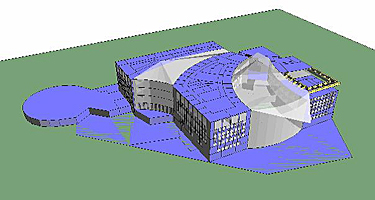

Building Information Modeling (BIM) was integral to the project's success. Given the complex design, construction of the iconic glass roof and curtain wall required dedicated teamwork from design concept to final installation. The design phase was unique, given it fully integrated BIM and final construction approval was based upon the 3D model rather than a 2D drawing set. In addition, the design-assist contract, which was awarded early in the design phase, allowed for maximum input from Clark and Seele.

Both the budget and design energy cases were modeled in Virtual Environment (VE 5.8), an energy simulation program, created by IES Ltd., which calculates the heating and cooling loads and the building energy usage for each hour of the year. The energy rates used for both the budget and as-designed cases were based on commercial sector average energy cost for Washington, DC ($0.071/kWh for electricity and $7.37/mcf for natural gas). The analysis was based on U.S. climate zone for the District of Columbia (Table D-1 of ASHRAE 90.1-1999), and the building envelope requirements prescribed in Table B-13 of ASHRAE 90.1-1999. TMY2 weather file Washington, DC was used for the analysis.

Left to right: Thermal model of Design Energy Case and Thermal model of Energy Cost budget case in VE 5.8

HVAC system modeling for the VAV unit with heat pipe.

PRODUCTS AND SYSTEMS

The expectation was that the building be a monumental design and construction of the highest quality. Materials and systems were selected for their durability to meet these goals, so that if properly maintained and repaired, should have a life consistent with other buildings on the National Mall.

As the building's organization emerged, the compositional massing and architectural expression were explored. Though the plan is dominated by the curvilinear wings which swing outward from the central pivot on 23rd St., the massing echoes the bilateral, symmetrical wings of Washington's Beaux-Arts style architecture. As seen from the Lincoln Memorial, the Institute is formed of identical wings. They are constructed of heavy masonry in the form of limestone-colored precast concrete. The base is slightly battered and then rises vertically. The bilateral symmetry of the massing repeats on the western façade, helping the structure turn the corner and to signal that it is the most recent structure on the Mall. The acid-etched concrete provides a highly finished surface with a rich texture similar to limestone, including sand aggregates and reflective mica particles.

Elevation and 3-D diagram showing precast concrete panelization.

Limestone was chosen for its aesthetic, light color, and durability. The limestone flooring found throughout the atria spaces was installed using a thick-set mortar to ensure its ability to stand up to the large amount of traffic it receives and ensure its long life.

Extensive use of limestone flooring in the atria spaces.

ENERGY ISSUES

A range of energy efficient measures were incorporated into the building to support lower energy use, increased comfort levels, and long-term cost savings.

-

High Efficiency Lighting: Average lighting power density for the office and meeting spaces is 1.3 W/sf versus 1.5 W/sf allowed by ASHRAE 90.1–1999 using Space by Space Method for offices. Average lighting power density for the exhibition space and auditorium is 1.3W/sf versus 1.5 W/sf allowed by ASHRAE 90.1–1999.

-

Additional Wall Insulation: The U– value for external walls in the building is 0.059 Btu/h–ft²–F versus 0.124 allowed by ASHRAE 90.1–1999.

-

Additional Roof Insulation: The U– value for Roof in the building is 0.044 Btu/h–ft²–F versus 0.065 allowed by ASHRAE 90.1–1999.

-

High Efficiency External Glazing: High-performance glazing (U – 0.28 Btu/h–ft²–F and SHGC – 0.33) was used for external glazing in the design case versus ASHRAE 90.1–1999 specified external glazing (U – 0.46 Btu/h–ft²–F and SHGC – 0.25).

-

High Efficiency Skylight Glazing: High-performance glazing (U – 0.49 Btu/h–ft²–F and SHGC – 0.33) was used for the skylight glazing in the design case versus ASHRAE 90.1–1999 specified skylight glazing (U – 1.17 Btu/h–ft²–F and SHGC – 0.33)

-

High Efficiency Condensing Boilers: Three condensing boilers with an efficiency of 96% were installed versus an 80% efficient boiler specified by ASHRAE.

One of three hot water boilers

-

Efficient Chiller: Three chillers with a better part load efficiency (IPLV - 0.332 kW/ton) was installed versus a centrifugal chiller specified as per ASHRAE 90.1-1999 (IPLV - .576 kW/ton)

Left to right: One of four chilled water pumps; chiller with reverse osmosis system and steam boiler.

-

Heat Recovery: Wrap around coil was used in the design case to pre-cool and pre-heat the air entering the zone. The energy transfer takes place due to evaporation and condensation of the refrigerant inside the coil, hence does not require additional energy from outside.

Energy Use Description

Site Energy Use Summary

Natural Gas: 3,319,180.2 kBtu (31%)

Electric—Grid: 7,540,939.2 kBtu (69%)

Total Energy: 10,860,119.4 kBtu

Energy Intensity

Site: 67.3 kBtu/ft²

Source: 168.3 kBtu/ft²

Emissions (based on site energy use)

Greenhouse Gas Emissions: 1,185.8 Metric Tons CO2e

Electric Meter

Total Consumption: 2,416,901 kWh

Total Consumption: 8,246,466.2 kBtu

Main switch gear in electrical room.

Natural Gas Meter

Total Consumption: 33,673 therms

Total Consumption: 3,367,300 kBtu

Data sources and reliability

Based on simulation? No

Based on utility bills? Yes

Power Generation Plant or Distribution Utility:

Potomac Electric Power Co [Pepco Holdings Inc.]

Natural Gas: Washington Gas

Comments on data source and reliability.

For electricity the data source is the energy management system (EMS) through Aquicore. They provide real time information for data-driven decision-making and streamlined processes. Pepco, the local electricity company, supplies the bills and information through their website which are used to track, compare, and analyze data. Both companies help take the system to the next level so that energy usage and data can be overlaid with calendar information and analyzed based on events and usage.

INDOOR ENVIRONMENT

Indoor environment approach

Code minimum ventilation and low VOC paints, fibers, and sealants all contribute to a healthy interior environment. Zoned climate control systems reduce heating and cooling energy use and improve indoor air quality. Outside and recirculating air filtration through the use of MERV 13 filters and the tighter building envelope reduce energy losses from infiltration while also reducing the possible entry of airborne hazards outside. Natural daylight also supports the goal of creating a healthy environment with the added benefit of the range of lighting quality and views that result from such large expanses of light.

PROJECT RESULTS

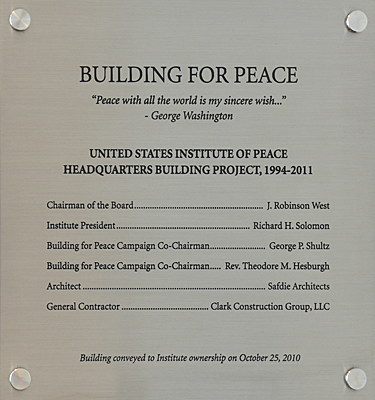

Building for peace sign is a visual reminder of the importance of the mission.

Lessons Learned

The Institute has transitioned from being a building tenant to an owner and manager of their own facility. This has greatly expanded their skills and role as leaders in combining the mission of sustainability and peace effectively and seamlessly.

The success of the project was made possible as a result of consistency across the team members during all phases and aspects of the project. This resulted in a higher level of commitment, integration, detail, coordination, and quality. The partnership with the architect, GC, and Akridge was instrumental in the success of the project.

Next for USIP

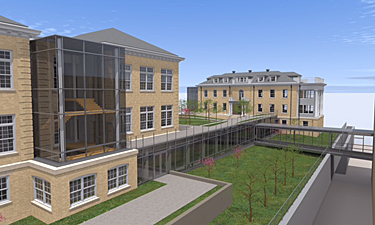

USIP is now poised to realize the full potential of the 3.0 acre campus they set out to build in 2011. The two neighboring historic buildings on "Navy Hill" are part of the campus that housed the first U.S. Naval Observatory and served as the original headquarters for the Central Intelligence Agency. USIP acquired the two buildings when the U.S. Navy relocated its Bureau of Medicine and Surgery operations from the Potomac Annex. USIP plans to rehabilitate the two 1910 buildings, called Building 6 and Building 7. The buildings will be used for offices, multipurpose classrooms, and conference space. Building 6 will house the Institute's Academy in flexible and technologically advanced classrooms. Building 7 will house the PeaceTech Lab in flexible meeting spaces and collaborative work areas.

The exterior of Buildings 6 and 7 require several repairs. The original wood cornice and balustrade will be restored and repainted. The brick façades will be repaired as necessary to ensure the integrity of the wall. The plan will remove an unsafe addition to Building 6 and replace several poorly installed windows at Building 7. The interiors will be fully rehabilitated to meet current life safety, accessibility, and energy codes with all new building systems, including mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and fire safety. The circulation will be upgraded to current standards with the construction of a new egress stair tower at each building. The new glass enclosed stair towers will be an architectural feature of the campus and will visually connect Buildings 6 and 7 to the Headquarters building. At Building 7, the stair tower provides balance and symmetry to the south facing original porch structure. At Building 6, the stair tower will bring natural daylight into the central breezeway, which will be used as gathering and lounge space. The design of the stair towers is intended to differentiate the new and historic. New elevators will be installed in both buildings. The design also includes an elevated pedestrian walkway to connect Buildings 6 and 7 to the Headquarters building and create a connected USIP campus. The enclosed walkway will span from the north side of the 3rd floor of the USIP Headquarters Building to the south side of the Annex site. The enclosed circulation will extend to an east-west oriented enclosed arcade which leads to 1st floor entrances at Building 6 to the west, and Building 7 to the east. The walkway and arcade will also serve as the ADA compliant pedestrian access to the Potomac Annex buildings. The east-west arcade will also act as a retaining wall to a newly formed plaza between Buildings 6 and 7. The plaza will provide additional outdoor program space for events.

Renderings of the Buildings 6 and 7 expansion and renovations.

USIP is committed to all facets of a better future. Each day the sun sets and the soft glow of the dove wings on the roof illuminate at night, reminding everyone of the commitment USIP serves and enabling the building to tell its own story. When the sun rises each morning, the team looks for new ways and challenges to keep pushing for a better world through peace and a commitment to a better environment. USIP continues to explore ways to maintain the sustainability and performance of the building to ensure that its success and leadership in these areas can be shared and communicated to the community and the world. The inspiring structure serves as an enduring legacy for peace in greatly facilitating the day-to-day work of the Institute.

Ratings

- LEED-NC Gold Certification, 2011

- Energy Star Rating, Score of 91

Awards

- 2011 Washington Building Congress Craftsmanship Award - Precast Concrete

- 2011 Washington Building Congress Craftsmanship Award - Curtain Walls

- 2011 Washington Building Congress Craftsmanship Award - Drywall

- 2011 Washington Building Congress Craftsmanship Award - Interior Stone & Marble

- 2011 Washington Building Congress Craftsmanship Award - HVAC - Sheet Metal

- 2011 Washington Building Congress Craftsmanship Award - HVAC - Piping

- 2011 Washington Building Congress Craftsmanship Award - Ornamental Metal

- 2011 Washington Building Congress Craftsmanship Award - Architectural Millwork

- 2011 Washington Building Congress Craftsmanship Star Award - Ornamental Metal

- 2011 NAIOP MD/DC Award of Excellence - Best Institutional (Award of Merit)

- 2011 ABC of Metro Washington Excellence in Construction Awards - Mega Project

- 2011 ENR NY Best Office Project

- 2011 AGC of DC Washington Contractor Award - Best New Construction Project - Award of Merit

- 2011 ENR Best of the Best - Best Office Project

- 2011 ACI National Capital Chapter Award of Excellence

- 2010 Washington Building Congress Craftsmanship Award - Concrete/Cast-in-Place Concrete

- 2009 Associated Builders and Contractors of Metro Washington - Excellence in Construction (Excavation/Site Work)

Publishing

- "Building Systems Deliver Data, Control at U.S. Institute of Peace," by Ronald Kovach, managing editor Building Operating Management Internet of Things Issue, October 2015.

- "Public Buildings Case Study: U.S. Institute of Peace Headquarters," by David L. Winstead, ESQ. BOMA Magazine, January/February 2015.

- "The United States Institute of Peace Headquarters," by David Winstead and Michael Graham. Urban Land Magazine, May 2014.

- "A Permanent Home for Peace," by Laura Raskin. Architectural Record. October 25, 2011.

- "At Peace Institute Groundbreaking, War Dominates the Proceedings," by Michael Abramowitz. The Washington Post, June 6, 2008.

- "Below the Radar: A Federal Peace Agency," The Editorial Board. The New York Times, June 12, 2008.

- "Designing for dignity," by Carol Strickland. The Christian Science Monitor, June 3, 2011.

- "Giving Institute of Peace a Chance," by Brett Zongker. Los Angeles Times. Associated Press, June 13, 2007.

- "Institute of Peace to build new HQ," by Suzanne White. Washington Business Journal, August 20, 2011.

- "Moshe Safdie Builds for Peace," by Katherine Gustafson. ArchitectureWeek, November 9, 2011.

- Moshe Safdie: Volume 2 (Millennium) by Moshe Safdie. pp. 17, 202. Mulgrave, Victoria: Images Publishing Group, ISBN 9781864701630. 2009.

- "Peace Institute Dedicates Hall to Ex-Ambassador," by Nathan Guttman. The Jewish Daily Forward. December 6, 2011.

- "Peace Institute prepares to 'give blessing' to architects," by Suzanne White. Washington Business Journal, November 19, 2011.

- "U.S. Institute of Peace already in expansion mode," by Sarah Krouse. Washington Business Journal, March 22, 2010.

- "U.S. Institute of Peace & Public Education Center," by Emporis.

- "United States Institute of Peace Selects Akridge to Manage Landmark Headquarters Building," . Akridge, October 6, 2010.

- "War Contractor Funds Peace Institute," by William Hartung. The Huffington Post, July 26, 2009.