General Information

Building Name: The Bullitt Center

Bulding Location: Seattle, Washington,United States

Construction Type: New Construction (including public and academic buildings)

Size: 52,000sf

Market Sector: Private

Building Type: Office

Delivery Method: Integrated Project Delivery

Total Building Cost: $30 million

Project Completion Date / Date Building Occupied: April 2013

Project Team

Architect

Ron Rochon

The Miller Hull Partnership

71 Columbia

Seattle, Washington 98104

206-682-6837

rrochon@millerhull.com

www.millerhull.com

Engineer

Paul Schwer

PAE Consulting Engineers

1501 E. Madison #600

Seattle, Washington 98122

Project Management

Chris Rogers

Point 32

501 E. Madison #400

Seattle, Washington 98122

Contractor

Casey Schuchart

Schuchart Construction

919 5th Avenue #650

Seattle, Washington 98164

Commissioning Authority

KBA Construction Management

11000 Main Street

Bellevue, Washington 98004

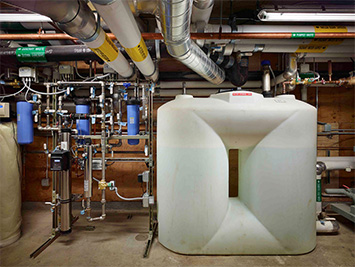

DESCRIPTION

Almost no buildings being built in the world now will make sense 30 or 40 years from now. We need a major leap forward and a quantum change in our environment. This building is a start—a wedge that will lead the way in transforming how we build our environments in the U.S. and around the world. Bullitt Foundation, CEO, Denis Hayes says: "The six-story, 52,000 SF Bullitt Center in Seattle, Washington, targeting Living Building certification—is one of the most energy efficient commercial buildings in the world—a high-performance prototype setting innovative standards for sustainable design and construction, demonstrating that it is possible to create a commercially-viable building with essentially no environmental footprint."

The Bullitt Center in its urban context.

Photo Courtesy of Nic Lehoux

The headquarters for the environmentally-minded Bullitt Foundation led by Earth Day founder Denis Hayes and other tenants, has achieved extraordinary levels of energy efficiency through integrated architectural and engineering design, cutting edge technology and components, non-toxic building materials, and conscious choices by tenants. The Bullitt Center also collects rainwater for potable and non-potable use. These elements reduce the six-story buildings annual energy requirement enough that it operates on energy provided by a roof top solar array and manages its own water and waste needs onsite, on an extremely tight urban block in rainy, overcast Seattle. As a living laboratory for net zero high-performance architecture, the building also serves as a center for sustainability education and seeks to change the way society views the relationship of a building to its environment. Interpretive displays in the building lobby explain the building and an online dashboard provides a window to real-time energy usage and other building functions. So far, energy performance is exceeding expectations. The building is operating net positive for energy, and is currently projected to remain net positive even when full occupancy is achieved. The success of this project hinges on a holistic approach to design and development. Beyond architecture, engineering and construction - to people and policy, the Bullitt Center models a new paradigm for sustainable urban commercial development.

Evaluation

Has the building been occupied for a minimum of 1 year following completion? Yes

Project Type: New Construction (including public and academic buildings)

Design trade-offs and interactions.

The audacious performance goals demanded a highly collaborative, inclusive, and integrated process encompassing the client, design team, engineers, contractor, suppliers, multiple jurisdictions, and the greater community throughout the design process. This ensured all participants understood and bought into the sustainability goals, and were clear of their role and responsibility in achieving the overall desired results. The project made good use of a substantial pre-design phase, where building size and massing, architectural and MEP systems, and renewable energy production potential were proven, prior to the start of schematic design. The complexity of this approach required a new design process based in BIM to effectively manage the systems as they evolved. Virtually every design decision made had to support the net-zero energy target. For example, to optimize the power production of the photovoltaic array, the team created a process through which parametric modeling software made it possible to quickly test different geometric solutions to achieve the highest power production. Another example is daylighting, which is an essential component of the net-zero requirements. Daylighting analysis drove not only the massing of the project, but the configuration of the curtain wall, skylights, and shading.

View of the building envelope and its overhanging photovoltaic array.

Photo courtesy of Benjamin Benschneider

How building materials, systems, and product selection addressed the design objectives, goals, and strategies.

From the onset of the design process, the team understood that for this place to be truly sustainable, it must be resilient, diverse, locally attuned and responsive, able to leverage interdependencies and allow for change over time. By connecting culturally, logistically and ecologically, this project set out to achieve an unprecedented level of sustainability.

Structure

Engaging staircase incorporating the warmth and character of wood.

Photo courtesy of Nic Lehoux

Heavy timber construction is the most visible structural elements, resurrecting a construction type that not attempted in Seattle since the 1920s. It was selected for its low embodied carbon; its history in Northwest construction, as well as for its beauty. While concrete was initially favored for the buildings super structure, a heavy timber frame was ultimately utilized for all areas where the structure wasn't either exposed to earth or wasn't required to resist seismic forces. The embodied energy of a timber frame is dramatically less than that of either concrete or steel, so wherever possible, wood was used resulting in a hybrid structure—concrete coming out of the earth, steel to resist lateral forces and timber for gravity loading conditions. Furthermore, timber is regionally sourced and building occupants have responded well to the warmth and character the wood provides in contrast to the windows and concrete. Due to the fact that most toxins in buildings today can be found in the finishes, the design purposefully kept materials as unfinished and close to their natural state as possible, i.e. the galvanized steel siding for instance was left unpainted, the timber received only a water based sealer to protect it during construction and aluminum was anodized and unpainted. Materials were sourced locally and construction processes minimized waste.

High-Performance Envelope

The building envelope greatly exceeds the Seattle Building Code requirements, using a triple-glazed curtain wall system that originated in Germany and is now produced locally. The well-insulated walls have been designed to eliminate thermal bridging and dramatically reduce air infiltration. Building massing and orientation, as well as glazing selection, control heat gain. To the extent possible on a compact, five-sided urban site, major glazing areas face south and north to improve daylighting and solar control. The building's windows, which open and close automatically in response to conditions outside, were selected for optimal control of heat loss and solar gain, while maintaining superb visibility for daylighting. Analysis shows that increasing the thermal performance of the envelope beyond current levels would have little overall impact on energy use in the proposed building.

Natural daylighting also allows for beautiful views.

Photo courtesy of Nic Lehoux

Closed-loop Geothermal System and Ventilation

The Center's very modest heating and cooling loads are met by ground source heat pumps and on-site geothermal wells. Water loops provide comfortable radiant heating and cooling to the office spaces. Ventilation is provided through a dedicated 100% outside air unit with an air-to-air heat exchanger, so that incoming fresh air is preconditioned by outgoing air.

Radiant floor heating and cooling with passive cooling and natural ventilation

Operable shading systems are designed for glare control to further mitigate solar heat gain. Operable windows provide free cooling and ventilation when ambient conditions are right.

Daylight Dimming and Efficient Lighting Design

Daylighting drove the architectural design and is the primary source of illumination in the building. Electric lighting loads in office spaces have been limited to 0.4 Watts per square foot, less than half the 0.9 W/ ft² currently allowed under the Seattle code. Automatic controls will dim or turn off the LED lights when daylight provides adequate illumination. However, daylighting is the primary lighting source so during most of the year those lights are off.

Open office spaces rely on natural daylighting as the primary source of illumination.

Photo courtesy of Nic Lehoux

Aggressive Reduction of Plug Loads

Plug loads for office equipment, such as computers, monitors, servers, printers, and copiers will be limited to a maximum of 0.8W/ft² (and this will be significantly reduced by plug load occupancy sensors).This is approximately half the 1.5W/ ft² typical for new office buildings, but it still allows for a computer-intensive environment. For example, in a typical high performance building, receptacle energy use may represent one quarter of the building total. In the Bullitt Center, about half of the energy use is expected to be in receptacles, even with the aggressive steps to limit power density and implement controls. Lease incentives for the tenants are used to ensure receptacle energy targets are met and to encourage tenants to employ the most efficient state-of-the-art equipment that meets their professional needs.

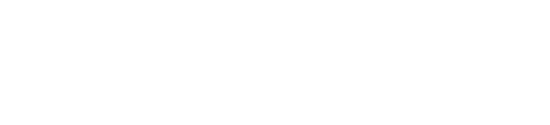

Net-Zero Water Approach

Approximately 69% (128,800 gallons) of the annual rainwater runoff is collected, stored in a 56,000 gallon cistern, treated, and used for potable and non-potable (approx. 11,400 gallons per year) uses; the remaining 31% will be discharged as storm water, ensuring the integrity of downstream hydrology. Approximately 100,600 gallons of grey water will be treated and evaporated/infiltrated onsite. Through a combination of infiltration, evaporation on the membrane roofing evapotranspiration on the green roofs, and piped discharge, the building closely mimics the historic hydrology of the site. The system supplies all non-potable water for building fixtures and is designed to meet all potable water needs when (pending) permits allow the building to use rainwater to supply 100% of its water needs. Human waste from foam flush toilets and urinals is delivered through piping to 10 basement composting units, where wood chips manage moisture levels and consistent temperatures (135°F to 165°F) ensure pathogens and contaminants are sterilized or killed. Each composter produces approximately 90 gallons (12 cubic feet) of compost each year. This valuable resource is taken to a nearby composting facility to be incorporated with other composted material, and used as a soil amendment.

Cistern for treating rainwater runoff.

Photo courtesy of Benjamin Benschneider

Composting units.

Photo courtesy of Benjamin Benschneider

How the project addressed existing site conditions and context including the surrounding community.

The ecological context for this project promotes density in established urban areas, and minimizing "and ideally, eliminating" the environmental impact of a building in an urban context. The Bullitt Center demonstrates an urban office building can meet its own water, waste and energy needs without adversely impacting the environment. The strict requirements of the Living Building Challenge stipulate that Living Buildings can only be built on previously developed sites. Previously, over half the site was an asphalt parking lot serving a one-story commercial structure. Considering the allowable density for the site was 52,000sf, the site was severely underutilized with just 4,000sf in commercial use. The project site was chosen for its high visibility and accessibility, in an area primed for economic development and targeted by Seattle's Central Area Action Plan for strategic neighborhood improvements to include: walkability, growth leveraging the adjacent connective corridor, sensitive infill, and creation of interesting urban spaces. The adjacent park was revitalized as part of the project into a vibrant public space, and an improved pedestrian crossing at the building's corner serves nearby retail businesses, schools and churches. To provide incentives for transportation alternatives, on-site building features contributing to reduced vehicular trips include secure, protected bicycle parking, shower and locker facilities. No onsite parking is provided. Although the building footprint occupies almost all of the 10,000sf site, building setbacks, foundational greenspace/landscaping, and an open courtyard utilizing a public right-of-way provide a welcoming transition to both the commercial corridor and residential neighborhood it straddles.

PROJECT RESULTS / LESSONS LEARNED

GOAL| A Model GOAL| Net-Zero Energy GOAL| Integrated High-Performance Based Design

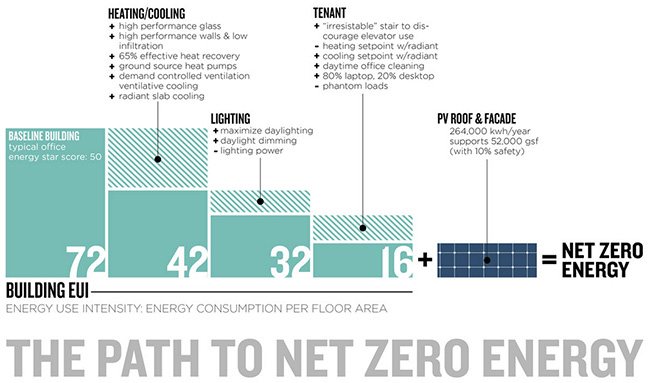

The prototype Bullitt Center models obtainable high-performance standards and is about sharing lessons learned to promote innovative sustainable building technologies and practices in Seattle's city neighborhoods, the Northwest, and worldwide. The Living Building Challenge requires net-zero energy on an annual basis. Toward this goal, the integrated design team was forced to go beyond state-of-the-architectural and engineering solutions to include high-performance envelope, geothermal heat exchange, lighting power reductions, maximized day lighting, heat recovery, hydronic heating, night flush ventilation, and engaging building occupants to further reduce their own energy loads.

Safe and Secure: Design and construct buildings that resist natural and manmade hazards. All materials and systems were vetted against a 'red list' of prohibited toxins. As most toxins in buildings are found in finishes, the design purposefully kept materials as unfinished and close to their natural state as possible (i.e. galvanized steel siding was left unpainted, timber received only a water-based sealer to protect it during construction and aluminum was anodized and unpainted. Although heavy timber framing is a prominent feature of the building, steel provides required structure to resist seismic forces prevalent in the earthquake prone Pacific Northwest. Bioswales and pervious pavement process and retain building storm water runoff on site to reduce pollutants entering the Puget Sound watershed, which benefits the region beyond the confines of its own footprint.

Productive/Healthy: Design for building occupant physical and psychological well-being. Consideration of the interior environment is essential to the success of the Bullitt Center. As no 'red list' materials with prohibited toxins were used, the building offers a clean, safe environment for occupants and visitors. Exceptional daylighting and operable windows providing fresh air for natural ventilation also contribute to a healthy and uplifting work environment. Daylighting for general area lighting also reduces undesired internal heat production. An exit stair reimagined as the irresistible stair, a transparent glass stairwell located on an outside wall of the building offering views of the city skyline, Puget Sound, and Olympic Mountains, encourages occupants to walk between floors for health benefits, provides opportunities to interact with others, and to offset the energy demands of taking an elevator. The result for occupants is a healthier daily routine, a stronger sense of community and the opportunity to impact in the reduction of energy use.

Bicycle racks.

Photo courtesy of Benjamin Benschneider

Accessible: Ensure equal use of the building for all and plan for flexibility. All spaces in the building and throughout the site are readily accessible. Open floor plates can be easily configured to suit changing tenants needs.

Aesthetic: Building massing was not driven by metaphor or aesthetics, but rather by performance metrics. In doing more with less, the design team identified imaginative ways to express the building's core functions and to creatively celebrate regional context and climate conditions through materials and features. Heavy timber framing leverages a renewable local resource that multi-tasks for strength, beauty and carbon sequestration. Floor to ceiling windows provide natural light and fresh air. In stretching the bounds of architecture to consider the building as functioning like a living organism, much like a flower that moves to follow the path of sun through the sky, the exterior solar controls deploy and adjust through the course of the day giving the building a dynamic, ever-changing character. The design team ensured sustainable features of the building are visible and on display, enabling the building to tell its own story. All systems are visible through glass walls in the basement of the building.

Instead of burying the grey water treatment deep within the building, a constructed wetland landscape is visible on a lower roof of the building's most prominent facade provides a pleasant green space amenity. Most visibly, the overhanging photovoltaic panel array on the roof which provides all of the power for the building is reminiscent of Northwest regional design vernacular.

Cost-Effective: Selection of building elements on the basis of life-cycle costs. One of the most sustainable buildings is a building that lasts. The building was designed to be easily taken apart over time as various systems require replacement or remanufacture. Core structural elements of the building are designed to last 250 years; keeping the heavy timber frame on the warm side of the thermal envelope eliminates the chance of moisture and rot. Windows and walls have an anticipated service life of 50 to 75 years after which the curtain wall and wall panels, which are simply bolted to the building, can be replaced without disrupting the structure. Active technologies—the PV panels and exterior solar controls—are expected to last around 25 years, so are attached as the last layer, which can be replaced without compromising the thermal envelope.

Other elements make the building flexible and resilient. The exposed timber frame allows for easy visual inspection and replacement of the beams and columns. By virtue of its size and slow-burning characteristics, heavy timber is inherently fireproof, avoiding the need for gypsum board or other applied fireproofing. Steel support structure for the photovoltaic array is bolted together and can be adjusted in the future as panel technology and efficiency improves (i.e. the roof array could be reduced). Open floor plates can be easily reconfigured, as required. Development of the Bullitt Center highlights the reality that modern building financing models ignore the external costs that developers have been able to pass on to the public without penalty for years. The Bullitt Center internalizes those externalities such as environmental pollution, carbon emissions, and lost productivity & health costs. For instance, the premium paid for FSC Certified Pure lumber throughout the Center protects salmon, saves topsoil, and meaningfully sequesters more carbon than wood sourced from traditional clear-cut forests.

The Center's photovoltaic array, funded by U.S. Treasury grants to offset the cost of the PV and waste treatment systems, mitigates the need for development of new, gas-fired power plants in Washington State. The Bullitt Foundation chose not to calculate simple paybacks for premiums to obtain Living Building status because those payback models illogically do not incorporate all external costs paid by society. Program goals included developing a market rate, leasable commercial building able to compete with area Class A office space. Rents are comparable to those for newly constructed, LEED-certified buildings in the area, and it eventually expects a positive return on investment. A rigorous analysis of the cost of the Center compared to the total cost of a baseline building forced to recognize its externalities will be published in conjunction with obtaining Living Building status.

Underside of the overhanging photovoltaic array from the stairway.

Photo courtesy of Nic Lehoux

Functional: Define the size and proximity of the different spaces needed for activities and equipment and anticipate changing information technology (IT) and other building systems equipment. The building was designed in keeping with the trend for open plan floor office space that can be easily configured to suit (the design team was not directly responsible for the bulk of post-completion tenant improvements).

Active technologies—the PV panels and exterior solar controls which are expected to last around 25 years given ongoing advancements in technology, are readily accessible so they may be updated as needed or whenever new systems warrant, and can be replaced without impacting the thermal envelope. Other elements make the overall building flexible and resilient; i.e. the photovoltaic array can be adjusted in the future as panel technology and efficiency improves (i.e. the roof array could be reduced) and open floor plates offer flexibility to suit tenant requirements.

Synergies

Collaboration is one of the hallmarks of this project, with innovations focused as much on the process as the final result. The integrated design team, along with the owner and contractor, worked together during the predesign phase that proved out the essential elements of net-zero energy, water, and other major goals. Meetings in this phase also involved interested members of the local design community, a city government-sponsored Technical Assistance Group, and other local leaders. This early scoping and design work allowed the essential design to be established early, with buy-in and support of many in the community. Integration extended to the tools supporting the design process. The team targeted an integrated approach that allowed for immediate performance feedback on design decisions. The use of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and technical analysis tools enabled a more iterative and fluid design process, encouraging active collaboration in response to the interconnectedness of project goals. Energy modeling set the general parameters for net zero energy design while parametric modeling to size and configure the PV Array determined how to architecturally incorporate renewables. Using the various project parameters and constraints the team set up a workflow utilizing the computing capacity and nimbleness of Sketch-Up, Rhino, and Grasshopper to quickly explore hundreds of iterations of PV array geometry and layout that would lead to the optimum location and inclination.

Roof-top photovoltaic array.

Photo courtesy of Benjamin Benschneider

Daylight modeling drove design and was used to calibrate lighting calculations in the energy model. In the past, daylighting and energy have been modeled separately; the project was actually the first to fully integrate daylighting and energy modeling. The building skin was also developed through a series of iterations in Grasshopper, controlling the amount of daylight, building form, and solar energy production. Using this combination of Sketch-Up, Rhino, and Grasshopper provided real time metrics for understanding the impact of the architectural decisions on the performance of the building. In order to optimize the window design relative to heat loss, heat gain, and daylighting, the qualitative aspects of daylighting and the quantitative energy savings provided by daylighting, as generated by the energy model, were tested and aligned using a spreadsheet tool developed by the University of Washington Integrated Design Lab.

Finally, the degree of integration between the comfort model and the energy model was also a first. A comfort and airflow model fine-tuned ventilation strategies and performance, and was linked to the energy model by supplying anticipated window opening and closure data. The models, which have typically been used separately, were essentially integrated so that the output of one model then became an input of the other. This allowed optimizing the operable window system so that energy consumption for cooling and ventilation could be minimized in the design. The team pioneered a process to review and approve materials use in conjunction with the Living Building Challenge materials red list requirements.

How the performance of the building was measured or evaluated.

During design, features that did not contribute to performance "however enticing" were dropped. The value of extensive modeling is being validated with post-occupancy analysis focusing on adherence to net-zero energy and net-zero water, indoor air quality, and occupant satisfaction. The building is being continuously monitored and analyzed. Real-time building systems and information about the building design, construction, and operations are available for review via an online dashboard, in reports and through project team public presentations. A post-occupancy evaluation survey of building occupants reviewed numerous aspects of the building from a user perspective which revealed that window design "scale, views, operability" is the second most important design feature that brings beauty and spirit to the project, after the exposed wood structure. Just seven months after it opened, the Bullitt Center achieved its target annual energy production levels. Other metrics point to favorable outcomes leading up to Living Building Challenge certification. There is a lack of good data on high-performing buildings in North America, but from the data that is available it appears the Bullitt Center will perform at the forefront of energy efficiency. The U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) High Performance Buildings Database currently contains no comparable buildings. The only urban commercial building is a single-story, 6,500 square foot lighting consultancy on the outskirts of San Jose, CA. The other net-zero buildings are nature centers, recreation centers, and classroom buildings, all but two of which (a 3,500 square foot tennis club and a 2,200 square foot instructional facility) have higher EUIs than the Bullitt Center. In the DOE High-Performance Building database, the Bullitt Center is significantly more efficient than any comparably sized urban commercial building currently listed.

How the owner/client and community benefited.

The Bullitt Foundation is a long-standing Seattle philanthropic organization seeking to make the Pacific Northwest a global model for prosperous, resilient equilibrium. With this building, the owner/client - the environmentally-minded Bullitt Foundation led by Denis Hayes, the founder of Earth Day - has a self- sustaining and commercially viable example of how buildings can positively impact both built and natural environments. Living up to its goal to be a teaching tool, since its opening in April 2013, 6000+ people have toured the building, including foreign heads of state, local/regional/state/U.S. government officials, design and engineering professionals, university-level as well as primary and secondary students. The building's interpretative space is also a popular event venue, hosting a range of corporate and organizational events, expanding its reach as an example of functional and educational space. The realization of this building also required close cooperation with local government, which altered regulations and zoning to enable many of its landmark sustainable strategies--which paves the way for other projects to follow. The location was chosen for its high visibility and accessibility, in a neighborhood that is predominantly residential, yet striving for economic and commercial development. Adjacent McGilvra Place Park is revitalized into a vibrant public space, and an improved pedestrian crossing of the busy thoroughfare corner where it resides serves nearby retail businesses, schools and churches.

Interpretive Center.

Photo courtesy of Nic Lehoux

How energy-related issues were addressed in this project.

Automated external shades.

Photo courtesy of Benjamin Benschneider

For the Bullitt Center, the decision was made to pursue guidelines outlined by the Living Building Challenge, the most rigorous green building certification program in existence. The Bullitt Center demonstrates that net-zero energy, meeting the goals of the 2030 Commitment, is feasible today in a mid-rise urban office building, using an integrated design approach, off the shelf technologies, and attention to occupant effects on building energy use. In targeting net-zero energy, the design team calculated how much energy can be captured on-site from the sun and the earth using good design and state-of-the-shelf technology. The Seattle climate is characteristically moderate with temperate summer highs and overcast skies during much of the year, with the majority of precipitation falling in non-summer months. The main climatic response was to design a building that could operate with no heating and cooling energy during the bulk of the year and which required lowering the heating balance point temperature through a thermally efficient building envelope coupled with heat recovery on ventilation air. On the cooling side, natural ventilation for passive cooling with a night flush capability, along with thermally massive floors, allows the comfort zone to be extended upward where there are only a few hours during the year where cooling would be used. For a 52,000 square foot, six story building on this specific site, the estimated energy to be captured and converted into heat or electricity was 16 kBTU/sf year. This considers conditions during all 8,760 hours in a year and included understanding the day-to-night temperature swings, rainfall, cloud cover, and the hourly availability of sun, wind, and light. With this understanding, the design team established climate design priorities and architectural design strategies.

Parametric modeling made it possible to quickly test different geometric solutions to achieve the highest power production. The building was then designed to use no more than that amount of energy. Daylighting analysis drove not only the massing of the project, but the configuration of the curtain wall and skylights to align with the perception of a sustainable Pacific Northwest building, in which daylighting alleviates extended cloudiness and operable windows provide an indoor/outdoor connection. Building width was limited to 70' to keep perimeter zones about 24' deep, surrounding a 22' core. Primary daylight facades face 30 east of south /west of north, an optimum orientation in the climate. Tall ceiling and window head heights (14' floor-to-floor) configured into large bands of clear glass, and appropriate window orientation maximize daylight penetration. Exterior dynamic shades control glare by cutting off low sun angles present in the 47° North latitude. The west facade is shaded much of the year by mature trees in the adjacent park.

Design intent targeted a 2% daylight factor over the entire work space under overcast skies. While not fully achieved in the final daylight model, in practice all work areas are extremely well day lit and general illumination is not necessary during daylight hours. Uniquely, the building's envelope is a dynamic, switch rich selective filter that adjusts to the conditions of the environment, rather than an indiscriminate barrier to the outdoor environment. Windows operate automatically when exterior conditions are suitable for natural ventilation and passive cooling. But that's not the whole story; beyond high-performance climate responsive design, a significant factor includes how people behave and use energy inside the building to meet the goal.

Numerous buildings features facilitate positive human behaviors that minimize energy use. So in a shift from a typical approach, design of the building was driven by performance, not by aesthetics, although ultimately the beauty of the building follows from the honesty and visibility of its sustainable elements.

Annual Energy Use by Fuel

Electricity: 236,400 kWh (from solar array)

Gas: n/a

Fuel Oil: n/a

Biomass: n/a

Other fuel: n/a

Total: 230,000 kWh

Annual Energy by End Use

Heating: 6,000 kWh

Cooling: 5,600 kWh

Fans & Pumps: 33,000 kWh

Lighting: 53,000 kWh

Domestic Hot Water: 7,800 kWh

Plus Loads & Equipment: 131,000 kWh

Other End Use: n/a

Annual On-Site Renewable Generation

PV: 257,800 kWh

Total: 257,800 kWh

Peak Use

Peak Electricity Demand: 40kw

Peak Natural Gas Demand: n/a

Peak Cooling: 1,000 ft²/ton

Connected Lighting Load: 0.4 W/ft²

Data Sources and Reliability

Based on simulation? Yes

If yes, list software and versions. eQuest, supplemented with manual calculations and ventilation modeling inputs

Based on utility bills? No

Comment on data sources and reliability.

Energy performance data is provided here based on a highly detailed energy modeling effort used to confirm extremely low energy consumption required to achieve net zero energy. The project has been occupied since February 2012 although tenants have grown into the building since that time. At the outset, occupancy rates were approximately 50%. The building is now 83% leased. Data from the onsite metering system shows that for the 12 months leading up to June 2014, actual energy use corresponded to an EUI of 9.4 kBtu/SF, compared to the design EUI of 16 kBtu/SF. So, actual performance is exceeding expectations. Adjusting for occupancy within the energy model suggests that even at full occupancy the EUI will likely not exceed 12 kBtu/SF which is significantly less than any comparable North American office building. The building's submetering system is not yet fully operational; system debugging is ongoing. As a result, actual measured end use performance data is not yet available. Visual study of the overall building consumption data vis-a-vis the energy model predictions suggests that the modeling has fairly accurately predicted HVAC energy but lighting and plugs were over-predicted, highlighting the importance of occupant engagement and user buy-in to established energy targets.

Mechanical room on display.

Photo courtesy of Benjamin Benschneider

How indoor environment-related issues are addressed in this project.

The Living Building Challenge requires products to be made without toxic chemicals and procured from regional sources. The red list determines which materials are prohibited on Living Building projects. The absence of VOCs and other toxic materials provides a clean, healthy environment for building occupants and visitors. Daylighting and natural ventilation goals drove building design to meet LBC requirements for a 'Civilized Environment' for all users; to reduce heating, cooling, and lighting energy use; and to align with the perception of a sustainable Pacific Northwest building, in which daylighting alleviates extended cloudiness and operable windows provide an indoor/outdoor connection. Tall ceiling and window head heights (14' floor-to-floor) configured into large bands of clear glass, and appropriate window orientation maximize daylight penetration. Exterior dynamic shades control glare by cutting off low sun angles present in the 47° North latitude. Design intent targeted a 2% daylight factor over the entire work space under overcast skies. While not fully achieved in the final daylight model, in practice all work areas are extremely well daylit and general illumination is not necessary during daylight hours. Windows operate automatically when exterior conditions are suitable for natural ventilation and passive cooling. Automation allows for window use during a night flush mode; manual overrides are provided in the space enabling occupants to adjust, as needed.

How the project addressed project-level and community-level resilience goals.

Most of the project goals around net-zero energy, net-zero water, and a long-life building structure with concepts of replacement of building and technology over time, are aligned with goals that promote resiliency. Natural ventilation, passive cooling, composting toilets, high-performance envelope that can provide thermal comfort even in periods of power loss, are all strategies that make the project more able to serve needs of users and the community over the long term. Furthermore, material choices that satisfied Living Building Challenge red list and radius requirements support resilient goals. Community-level resilience is addressed through the project's role as a demonstration of how resilient strategies can be incorporated into projects in a replicable economic model. The project also serves to demonstrate how some resiliency goals and resilient design strategies could be developed at a community rather than a single-building level.

References

To meet the aggressive goals of the Living Building Challenge, the project team targeted an integrated approach that allowed for immediate performance feedback on design decisions. The use of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and technical analysis tools enabled a more iterative and fluid design process, encouraging active collaboration in response to the interconnectedness of project goals.

Bringing together disparate design expertise and perspectives, BIM helped forge a common language in which design decisions could be evaluated and communicated in the context of the overall project goals. BIM was used as a funnel to control information, acknowledge constraints, and keep design concepts accountable and on track toward development of the staggering set of systems to achieve the most ambitious benchmark of sustainability in the built environment. Overall, the use of BIM programs and modeling were invaluable assets which informed all projects stages including exploration and evaluation, confirmation, coordination, and execution of the final building.

Design Software: Array

Energy Simulation Software: eQuest (energy modeling)

Benchmarking Software / Methodology: CBECS, EPA Target Finder

Other Tools: TAS; Ecotect; Rhino/Grasshopper; PV Watts

Ratings

- Living Building Challenge Certification (International Living Future Institute)—January 2015

Awards

- Honor Award: 2014 Sustainable Building Industry Council Beyond Green Awards, Category A: High-Performance Building

- Architizer A+ Awards, Finalist & Special Mention—Architecture + Sustainability, 2014

- World Architecture News, Sustainable Building of the Year Award, 2013

- Green Dot Award, Excellence in Green Services Award, 2013

- Wood Design & Building North American Wood Design Awards, Citation, 2013 U.S.

- Woodworks, Wood Design Awards, Best Multi-Story Wood Design, 2013

- ENR | National, Best Project of the Year, 2013

- ENR | Northwest, Best Green Project of the Year Award, 2013

- AIA Northwest & Pacific Region, Special Jury Recognition, 2013

- Metal Architecture Magazine, Sustainable Metal Building of the Year, 2013

- Architizer.com A+ Awards, Finalist & Special Mention, Architecture + Sustainability, 2013

- Forest Service Council, Design and Build with FSC Wood Award, 2012

- Seattle Business Magazine Washington Green 50, Special Project Citation, 2012

- AIA Seattle, What Makes it Green? Award, 2012

- EcoStructure Magazine, Evergreen Award on the Boards category, 2011

Publications

- "How One Building is Changing the World," Grist, October 14, 2014.

- "Sustainable in Seattle: A Deal to Meter and Finance Energy Efficiency," Huffington Post, October 7, 2014.

- "Report finds $18.5 million in hidden value at Bullitt Center," Bullitt Center.org, September 2014.

- "Life Inside a Living Building," gb&d | green building & design, May/June 2014.

- "Seattle's Bullitt Center Shines," Architecture Record, May 1, 2014.

- "Ultra Green Building is Ready for Challenge," Seattle Times, April 27, 2014.

- "Unveling the Secrets Behind Seattle's Bullitt Center"CNN, , April 22, 2014.

- "A Vision for the Earth," Alaska Airlines Magazine, April 2014.

- "Insider Guide: Seattle—The Bullitt Center," Sunset Magazine, April 2014.

- "Bullitt Center: Seattle's Net-Zero Energy Building"Engineering.com, , March 30, 2014.

- "Bullitt Center Rises to the Green Building Top," EarthTechling, December 30, 2013.

- "The Miller Hull Partnership wins WAN Sustainable Building of the Year," World Architecture News, December 27, 2013.

- "Year in Review | Most important Capitol Hill Stories of 2013"Capitol Hill Seattle Blog, , December 23, 2013.

- "Are Toxic Chemicals in Building Materials Making Us Sick?," Huffington Post, December 12, 2013.

- "An Environmental Model for the Next 250 Years: Seattle's Bullitt Center," Urban Land Magazine, November 2013.

- "Eco-nomics 101: the Washington Green 50 know that being 'green' and 'in the black' aren't mutually exclusive," Seattle Business, November 2013.

- "12 Landmarks of Seattle's future," Crosscut, October 21, 2013.

- "Heavy timber to rise again in construction," Minneapolis Star Tribune, September 19, 2013.

- "Best Citizen: Denis Hayes," Seattle Weekly, August 6, 2013.

- "Inside the Greenest Commercial Building in the World," Fast Company Coexist.com, August 1, 2013.

- "Yelp Review of the Bullitt Center," Yelp, July 2013.

- "Miller Hull Partner Ron Rochon on How the Bullitt Center Could Change Design," Ecobuilding Pulse, June 25, 2013.

- "Making Energy Efficiency Attractive for Owners of Older Seattle Buildings," New York Times, June 19, 2013.

- "Seattle's Bullitt Center - The World's Greenest Office Building," Interior Design, June 2013.

- "A Deeper Shade of Green," Architectural Record, June 2013.

- "America's Greenest Office Building," BuildingGreen, May 21, 2013.

- "Design Perspectives: The Bullitt Center starts out on a 250–year journey," DJC Seattle, May 15, 2013.

- "Blueprint for Change: A Seattle office building aims to be self-sustaining, offering a new model for urban projects," GreenSource, May 2013.

- "Seattle's Miller Hull Bullitt Center Highlights Sustainable Architecture," ecopedia, May 2, 2013.

- "Bullitt Center, supposedly world's greenest office building opens," Seattle Times, April 23, 2013.

- "Opening on Earth Day, a Seattle office claims to be the world's greenest commercial building," Architectural Record, April 22, 2013.

- "Seattle's Bullitt Center: Ready To Debut as World's Greenest Office Building," Northwest Public Radio (NPR), April 18, 2013.

- "How to Build a Greener Building," Popular Mechanics, April 10, 2013.

- "A Building Not Just Green, but Practically Self-Sustaining," New York Times, April 2, 2013.

- "The Bullitt building follows nature's lead in elegant efficiency," The Seattle Times, January 27, 2013.

- "Seattle Architects Design First U.S. Office Building Without A Carbon Footprint"Architizer.com, , January 22, 2013.

- "Seattle's new Bullitt Center May be the Greenest Office Building Ever"Good.com, , January 13, 2013.

- "The Greenest Office Building in the World is About to Open in Seattle," Fast Company, January 11, 2013.

- "New life for living building ideas," DJC Portland, OR, November 29, 2012.

- "Special Section | The Bullitt Center: A new prototype for urban green buildings," DJC Seattle , November 29, 2012.

- "Designing the Worlds Greenest Office Building," UW Arch [Be]log, November 14, 2012.

- "Five Greenest Buildings in the World," EarthTechling, September 1, 2012.

- "Seattle office building touted as greenest commercial structure in the world," Green Building & Sustainable Strategies, Number one; , August 31, 2012.

- "Greenest Commercial Building on Earth Rises in Seattle," Crosscut, July 23, 2012.

- "Here's to Your Health: Linking the built environment and wellness," GreenSource, July 2012.

- "Seattle's Newest office building will be completely off-grid"Revmodo, , June 25, 2012.

- "Seattle's Silver Bullitt: A New Office Building," TIME Magazine, June 20, 2012.

- "Predio superverde: Super Green Urban Building," Planeta, June 2012.

- "New Bullitt Center strives to show what 'green' can be," Puget Sound Business Journal, June 1, 2012.

- "City Encourages Living Buildings," Sustainable Communities, June 2012.

- "Five of the World's Most Sustainable Concepts," Green Building Elements, May 21, 2012.

- "President of Bulgaria Visits Seattle," Seattle Daily Journal of Commerce, May 17, 2012.

- "Big Challenges posed by living buildings," DJC Seattle, May 13, 2012.

- "Getting Greener: Seattle's Eco-District Nearing Reality," Architect's Newspaper | The West, April 28, 2012.

- "Are you up for the Living Building Challenge?," San Diego Source Daily Transcript, April 13, 2012.

- "Living Buildings: Can Bullitt inspire more?," DJC Seattle, February 16, 2012.